Most students use social networking and microblogging as a distraction — a break from reality, and a way to tell your best bud what you’re having for dinner tonight.

However, recent events in Egypt, Libya and Tunisia have sparked a change. What used to be the social network is now becoming a political network as well.

“Six hundred years ago, people used pigeons to send messages, because they were useful,” said Clarke Weatherspoon, a history teacher at Urban who held a lunchtime forum on Feb 10 as the Egyptian government fell. “Now, the most functional way of getting a message and idea out is social networking and access to social media.” A look at three countries — Egypt, Libya and Tunisia — shows how the social network is quickly becoming a network of politics and planning.

Tunisia

In Tunisia, an organization called SBZ News, a news agency of 15 cyber-savvy activists and reporters, kept everyone up to date with Facebook posts of photos and videos, along with Twitter updates from sources all over the country.

A key member of this organization, who identified himself as “Ali” to Newsweek magazine, said that while he knows what he does is dangerous, he is ready “to feel free—and to say what (he) believes.”

Facebook groups such as “Solidarity with the Jasmine Revolution: Democracy in Egypt and Tunisia,” also were created.

Andy Carvin, who heads National Public Media’s social media desk, said in an e-mail interview, “I think it’s rather simple – many of the young people who mobilized the revolutions are digital natives and don’t distinguish between their online and offline lives. Not using Facebook for them would’ve been as strange as patriots in the US revolution not using pamphlets.”

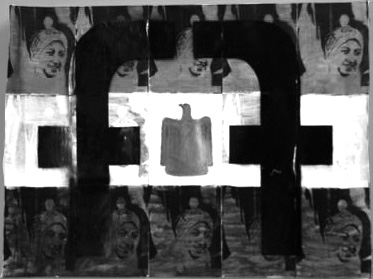

Egypt

An article in the Huffington Post noted that the initial protests in Egypt, like the Tunisian protests, “went out on Facebook and Twitter, with 90,000 saying they would attend.” Organizers also used social networks to produce live-feeds with “minute-by-minute instructions on where demonstrators should go in an attempt to outmaneuver the police.”

On Jan. 27, the Egyptian government shut down the Internet. Weatherspoon called the move “a mistake, as it “brought people into the streets because they wanted to know what was going on (outside).

“From a control perspective, as an authoritarian government, it’s better to have people blogging about how much things are a mess, than have people out in the street,” Weatherspoon said.

Following the shutdown, an organization known as Telecomix, dedicated to “collaborat(ing) on issues concerning access to a free Internet without intrusive surveillance,” immediately took various actions to keep people updated on unfolding events.

Libya

“Facebook Bus for Libyan Revolution 2011” has more than 2,200 members. And groups like this are exceptionally active, with long forums and discussion topics being commented on by people all over the world.

Carvin noted that even though in Libya, less than five percent of the population has Internet access, “Facebook helped get user videos and photos out to the international community.”

According to a survey of Urban students and faculty, 42.2 percent of Twitter users now use it for news updates. Several have been using it recently to follow the “Middle East revolutions,” one respondent said.

What the future holds

The horrific earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan on March 11 proved the power of the social network. Though phone lines and cellular networks were knocked out in the chaos, people were still able to communicate with friends and family online.

In one minute, approximately 28 tweets involving keywords “Japan” and “Tsunami” were recorded via TweetDeck, an application that collects tweets by subject. That’s about 1,680 tweets an hour, or 40,320 a day. If the average tweet is 23 words long, than that’s 927,360 words about a certain topic. Facebook has more than 500 million active userswith a combined 7 billion minutes on Facebook a month.

Social media is quickly becoming a useful tool and platform for the voice of the people. “For some occasions, like the Oscars or the Super Bowl, these networks basically become the world’s largest couch, where everyone is hanging out and talking. During a revolt, they become the world’s largest protest rallies and opposition headquarters,” said Carvin.