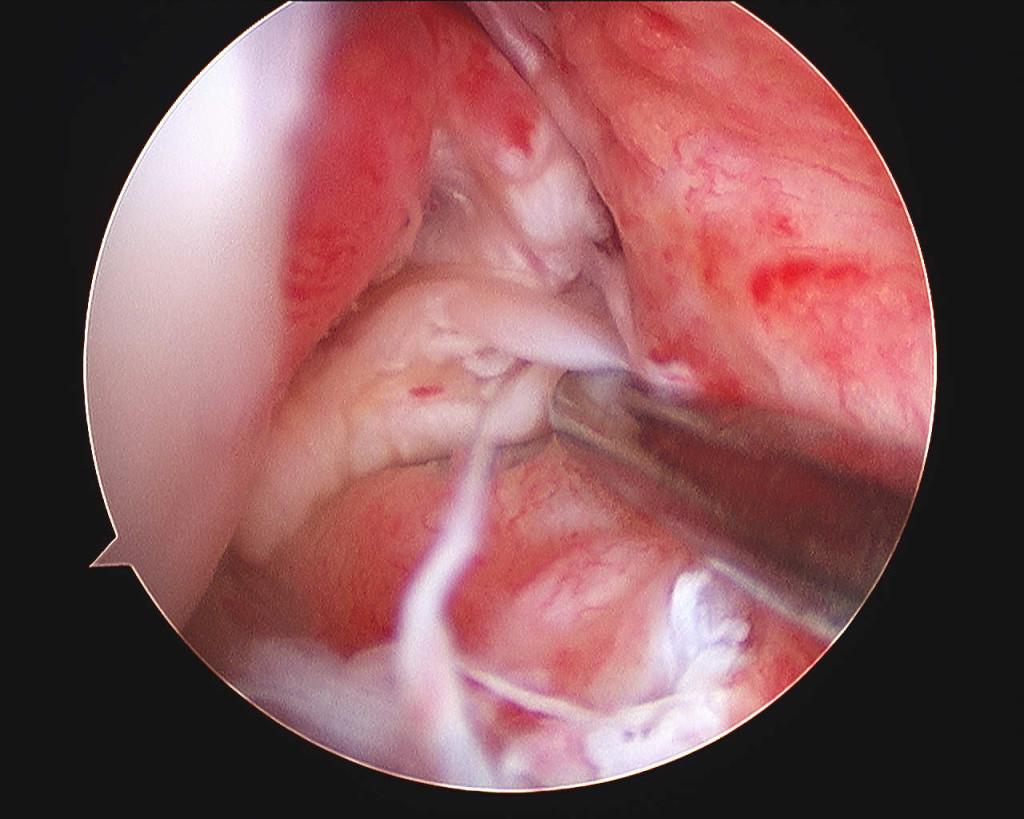

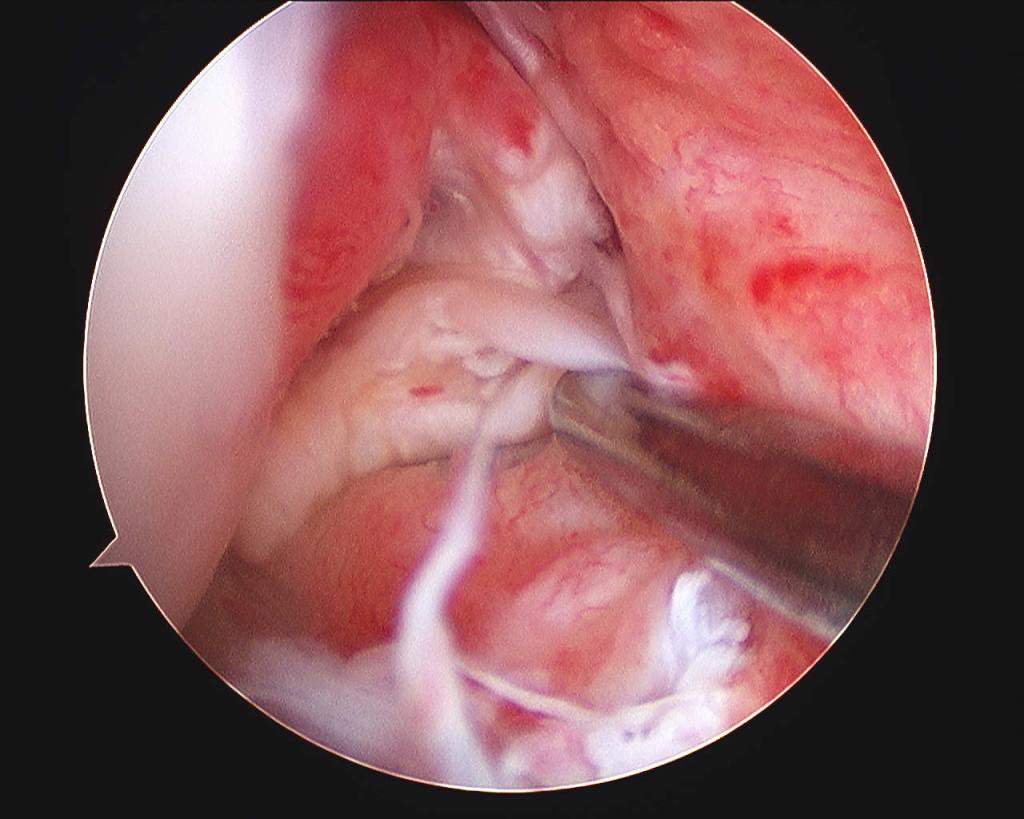

A photo taken of the inside of Colorado-Caldwell's knee during surgery reveals the shredded ACL

surgery video 1 She had done it thousands of times during practice and games. The jump stop was a simple technique that displayed her basketball skills and tricked opponents. As she stepped out onto the court on Saturday, Aug. 21, she felt nothing different. Without hesitation, she started to practice.

She had done it thousands of times during practice and games. The jump stop was a simple technique that displayed her basketball skills and tricked opponents. As she stepped out onto the court on Saturday, Aug. 21, she felt nothing different. Without hesitation, she started to practice.

She had done it thousands of times during practice and games. The jump stop was a simple technique that displayed her basketball skills and tricked opponents. As she stepped out onto the court on Saturday, Aug. 21, she felt nothing different. Without hesitation, she started to practice.

What happened next was out of her control. Jayne Colorado-Caldwell (’12) abruptly stopped during a shooting drill, her knee twisted, the bones sliding in different directions. As she would later learn, Colorado-Caldwell had torn her anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and strained several other ligaments in her knee.

Colorado-Caldwell is not the only Urban athlete to experience a sports injury. Gabriel Howden (’11) tore a ligament in his hip last season. In a soccer game against Stuart Hall, Howden went in for a hip check against the opponent. He heard a pop, tried to run it off, heard another pop, and collapsed.

Howden started to feel nauseous and was rushed to the hospital immediately. “I knew it was pretty bad because I couldn’t walk it off,” Howden said.

Colorado-Caldwell’s experience with the pain was different. She was at a basketball camp at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and went first to the camp medic, who said it was not a big deal. Colorado-Caldwell didn’t confirm the ACL tear until she came back to San Francisco to visit her physical therapist and get an MRI.

“I was sad, disappointed and angry,” said Colorado-Caldwell. She had worked hard all summer, training five days a week, either lifting weights at the gym or shooting hoops.

Carly Kuperschmid (’12), a teammate of Colorado-Caldwell, was very upset when she heard the news of the injury. “At Urban, athletics are based (on) dedication and hard work,” said Kuperschmid. “When a player has been showing these assets all summer to improve for the upcoming season, and then an injury prevents them from playing, it really sucks.”

Colorado-Caldwell worries about staying emotionally strong because she “will still be part of the team but won’t be able to play.” Howden, who had similar feelings of being left out, said he “eventually got used to it, but it was difficult to stay cooped up so long.”

After their injuries, both athletes also faced social and academic struggles. “It was really hard to focus in class because of all the painkillers I was on,” said Howden. Colorado-Caldwell says that her immobility will prevent her from going out with friends and will make her “social life plummet.”

Howden’s advice to anyone with a sports injury is to “take your time to get fully healed.”

Colorado-Caldwell cannot run for four months, and won’t be able to play any contact sports for six months. After an ACL tear, “there are three main treatment goals,” according to WebMD, including “to make the knee stable if it is unsteady… make the knee strong… (and) reduce the chance that your knee will be damaged more.” To meet these goals, Colorado-Caldwell will have to complete six months of physical therapy.

Teen sports injuries have become a huge national issue. “Surgeons and physical therapists say they see an epidemic of overuse — fractures, tears, and worn-down joints — in children who are playing at higher intensities and at younger ages,” wrote Kay Lazar for the Boston Globe in June.

Experts advise cross training to encourage young athletes to “branch out and try one or two other sports that would help build up other areas of the body and give the overused parts a break,” according to Lazar.

Greg Angilly, Urban athletic director, encourages athletes to try new sports to stay in good physical shape. Urban now offers yoga and mat Pilates to keep athletes flexible.

Another solution that Angilly has proposed is to hire a trainer to come to Urban every day at 2 p.m. to tape ankles, help athletes stretch out, and address of medical concerns. Athletes who have to leave class early for games would meet with the trainer before leaving campus. Another idea is to have an emergency medical technician (EMT) present at high-contact games, such as basketball and soccer.

Anthony Luke, a primary care sports medicine specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, is an expert on teen sports injuries; he works as an EMT for the San Francisco public schools. Luke has worked with a wide range of athletes, from professionals at the 2010 Winter Olympics to high school students struggling with injuries similar to those suffered by Urban students.

According to Luke, cross training is key to preventing injury. “If you are a runner, for example, it’s not always a good idea to just run; it might be a better thing to play soccer and (to) get strong moving side-to-side, and (to) work on your coordination,” said Luke. “Some of the pro athletes often played multiple sports when they were in high school, and benefitted from learning the skills of every other different sport.”

However, if an athlete gets injured, it is even more important that they stay healthy. “The number-one risk factor for an injury is previous injury,” said Luke. Just as Howden said, taking time to heal is vital.

When asked what Urban can do to prevent injury, Luke emphasized that “education and then implementation of the information that you learn is key.”