An industry in crisis: exploring the truth behind recycling

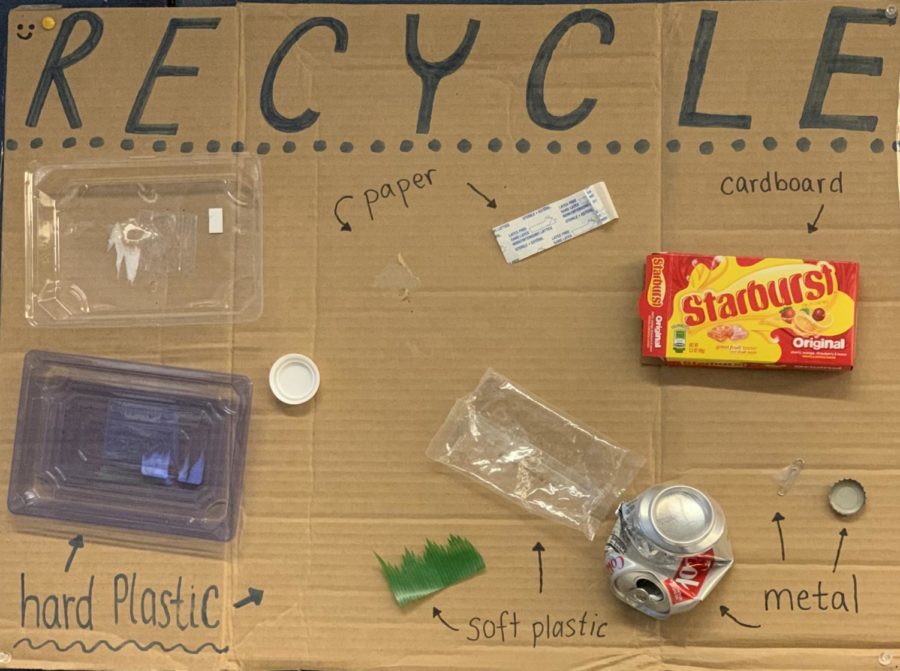

Green Team’s poster guide to recycling. Photo Credit: Ellie Lerner

Black bin, green bin, and blue bin; a wrapper here and an orange peel there. In the midst of a nationwide recycling crisis, it might be time to revisit our approach to waste sorting.

Until recently, American consumers have not had to face the repercussions of their recycling habits. For the past 25 years, China has imported and processed over a quarter of the world’s recyclables. However, according to an article published by Resource Recycling Inc., in the one year since China enacted its “National Sword” policy, the country’s plastic imports have decreased by 99%. Beginning in January 2018, this policy placed stringent regulations on recycling imports, limiting the accepted contamination rates — the percentage of trash mixed with recyclable items — to 0.5%. With an average contamination rate of 25%, as reported by Waste Management, waste collecting facilities across the United States are experiencing a large overflow of recycling with little recycling infrastructure to fall back on.

Despite having invested in recycling infrastructure in recent years, California has not been immune to the effects of the declining recycling industry in the aftermath of China’s recycling ban. As of August 4th, 2019, RePlanet, the largest chain of recycling centers in California, closed all of its 300 statewide locations. With the collapse of the recycling market, it is now cheaper to simply dump recyclables into landfills.

In contrast to the rest of the state, whose recycling rate dropped from 50 percent in 2014 to 44 percent in 2016, San Francisco’s waste management company, Recology, estimates that 85% to 90% of the materials San Franciscans toss in their blue bins are still getting recycled. This is in part due to 20 million dollar investments made in sorting technologies, including artificial intelligence, at the San Francisco Recology plant at Pier 96 throughout the past three years. While many other cities have completely shut down their recycling programs, Recology public relations manager, Robert Reed, reaffirmed that “San Francisco remains committed to reducing and recycling plastics.”

Despite rising to meet the most recent recycling obstacles with technological advancements, the demand for harder-to-sort film plastics (like plastic bags) and products with mixed materials (like plastic clamshell containers) has significantly decreased. Reed explained that “we continually see more plastic clamshell containers for salads and other takeout foods in San Francisco, but [Recology now] only receives one penny per pound for sorted and baled plastic clamshell containers.”

Some argue that the solution to the recycling crisis is bettering the way that consumers sort their waste in order to decrease contamination levels. Without proper recycling education, consumers are in danger of “wishcyling,” a term coined to describe the way in which eco-conscious consumers attempt to recycle items that are not actually recyclable. Susan Robinson, Director of Public Affairs for Waste Management, wrote in a 2018 article, “The Dangers of Wishcyling,” that “we all must focus our efforts on recycling the right items the right way.”

In recent years, Urban’s Green Team has attempted to increase the Urban community’s awareness around sorting waste. The group has hung up 3D posters around the school with instructions for where to throw commonly missorted items, as well as implemented TerraCycles, a subscription-based program that recycles products that cannot be recycled in traditional recycling plants. However, one particular challenge has been improper waste sorting in classrooms where there is usually only one type of bin.

As Sophia Stephens ‘20, a student leader of Green Team, explained, “a lot of people don’t want to take the few seconds to walk out into the hallway and dispose of their waste properly, and so they’ll dump all their trash into the compost bin that happens to be in that classroom.”

Although improving waste sorting has been a priority for Recology and Urban’s Green Team, Stephens contends that “we really need to look at where the waste is coming from in the first place and try to reduce that.”

Even before China’s recycling ban, only 9% of discarded plastics nationwide were being recycled, 12% were burned, and the rest were buried in landfills or simply dumped into rivers and oceans, according to an article published by the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. While proper sorting may help streamline the recycling process, the recycling crisis goes beyond sorting our greasy pizza boxes into the trash bin.

This past year, Senate Bill 54 and Assembly Bill 1080, known as the Circular Economy and Plastic Pollution Prevention Act, would have made California the first state to phase out single-use plastics. These two bills outlined the elimination of 75% of single-use containers across the State by 2030. SB 54 and AB 1080 include a ban on single-use products made from unrecyclable material as well as new manufacturing regulations that would require all California utensils to be recyclable or compostable. However, on September 16th, State legislators failed to pass these bills as this year’s legislative session came to a close.

While San Francisco’s recycling has not been significantly impacted in comparison to the rest of the country, this recycling crisis brings to light the way in which the blue bin allows us to excuse both consumers’ destructive consumption habits and manufacturers’ overproduction of plastics. “We can all do our own part,” Stephens said, “on an individual level with our choices and [on] a larger scale to pressure companies to change their practices to reduce waste.”