The deadliest act of anti-Semitism in American history

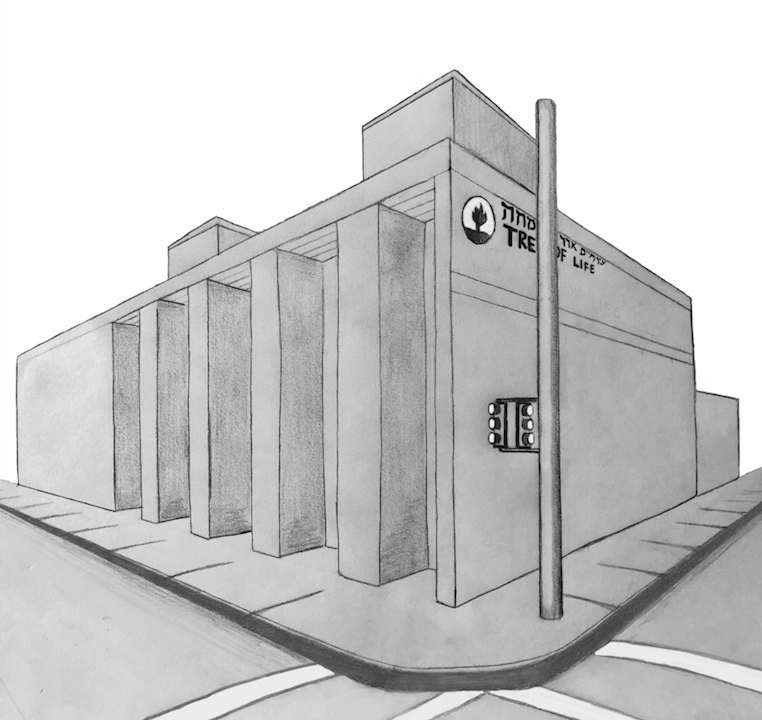

Illustration of Tree of Life synagogue, by Loki Olin, Features Editor

The shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh was the deadliest act of anti-Semitism in American history. On Oct. 27, 11 lives were lost when a gunman open fired during Saturday morning services.

Detective Sergeant Jim Glick, who was on scene during the shooting, said, “At first, I wasn’t sure it was real.”

Where do we go from here? Where do I go from here? Being Jewish is a core part of my life and I was heartbroken when I heard about the shooting at Tree of Life synagogue. It is hard not to feel powerless when a tragedy like this occurs. I turned to my friend and fellow journalist David Wilensky, Online Editor of The Jewish News of Northern California (The J.) for some insight into the power of journalism in moments like these. He said that “one of the nice things about journalism is that when there is a big crisis, you have something to do.” So I decided to do something. I wanted to try to figure out why the shooting occurred, to learn about the long history of anti-Semitism in America and to become more aware of how Jews and community members are personally affected by the shooting and how we can all help one another.

Jewish Studies Professor Marc Dollinger of San Francisco State University said, “ [the shooting] was unsurprising, because sadly with gun violence, and the rise of anti-Semitism, we knew this was coming someday.”

Dollinger talked about the increasing acceptance of anti-Semitism since the election of President Trump. “[Anti-Semites] have always existed in our society and they have been on the margins. They’ve always been shunned. What Trump and the Trump Administration have done is made it respectable and acceptable to have those views,” Dollinger said.

While anti-Semitism is becoming more and more apparent, the white privilege that white Jews have cannot be forgotten. “Most Jews appear white, so there’s a great deal of privilege in our community. During the 50s and 60s, white Jews became white people in America. But anti-Semitism didn’t go away,” Wilensky said. “A few days after the attack, there was a campaign mailer from a local Republican candidate in Maryland and his opponent is a Jew and it showed a picture of the guy holding wads of cash, which is just classic anti-Semitic imagery.”

In addition to the more contemporary anti-Semitism, Wilensky also commented on the American understanding of global anti-Semitism: “A lot of Americans are uncomfortable naming anti-Semitism because they thought it was gone. I think that a lot of Americans aren’t really educated about the history of it. They think that the Holocaust is this one-off. They don’t know about the long history of anti-Semitism before and after it. They don’t know that for instance, during the Holocaust, the United States turned away ships of Jewish refugees, sending them back to Europe.” Through my conversation with Wilensky, I was able to learn more about current anti-Semitism and how it is more widespread than I had thought. Additionally, I was able to put anti-Semitism throughout American history in context alongside the Pittsburgh shooting.

In the face of such a large tragedy, even if you are not from the targeted group, it can be hard to know what to do next. In an interview with the Urban Legend, Rabbi Jonathan Berkun, whose father, Rabbi Alvin Berkun, works at Tree of Life synagogue, shared some insight about what communities need after tragedies such as these: “When something happens with a specific group, it’s very very important to let them feel that they are not alone. That’s part of the pain that people have after a tragedy, the feeling of being alone. Not just physically being alone, but spiritually being alone.”

In an interview with the Urban Legend, Detective Sargent Glick shared some insight into how the shooting has affected his community differently than it has affected him personally. As a Detective Sargent, Glick had been prepared for a tragedy such as the Tree of Life shooting. However, the community was not. Glick expanded on this idea by saying, “They’re scared. Whether it’s a synagogue or a church or a mosque, or any place of worship, you would think that it’s a safe place. Well, now it’s not. I don’t want to say now that it’s not because it really still is, but in people’s minds, if that’s not safe, what is?”

To find out more about how the Pittsburgh shooting affected Jews at Urban please see the article in the print issue coming out before winter break.