Urban flunked the citizenship test. What does it mean?

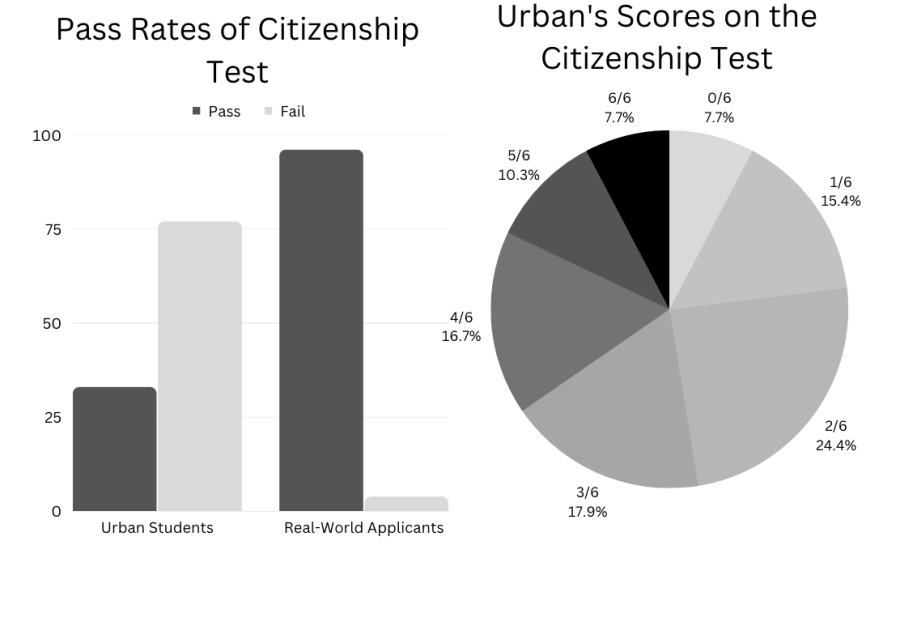

All applicants for citizenship in the United States are required to pass a 10-question citizenship test on the basics of American history and government. A score of 60 percent is required, and 96.1 percent of candidates pass. When Urban students took the test in a survey from The Urban Legend, however, a mere 30 percent of them made the cut.

When asked to name just one American territory, students offered Alaska, Hawaii and Cuba. Others submitted comedic responses out of pure confusion, saying that “Eagles, b****s, money and freedom of speech,” and “Stay strapped or get clapped,” are the supreme laws of the land.

The citizenship test is made up of 100 questions with set answers that are specifically outlined on the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services website. The test is heavy on memorization, including questions like the location of the Statue of Liberty, the impact of Susan B. Anthony and what wars the U.S. fought in the 1800s.

Many of the comical survey responses were due to the fact that the questions stray far from what is covered in the history curriculum at Urban. “Yea, I’m taking the L, man,” wrote Benjamin Chan ‘23.

“I did not know any of this,” wrote Laia Trachtenberg ‘26.

While Urban has pride in its focus on interpretive teaching and a learning-how-to-learn model, students fell short in the majority of the basic questions on the test. Only 22 percent of students could name how many members are in the House of Representatives, while only 41 percent of the student body could name the U.S.’ main concern during the Cold War. 17 percent of students could not name a single U.S. territory.

“I have no idea if [my] answers are right,” Camryn Saydah ‘23 said. “I feel like I don’t deserve the right to be a U.S. citizen if my answers are mostly wrong.”

These results pose an important question: are the topics on the citizenship test irrelevant and random, or does the privilege of those born into citizenship simply prevent our student body from knowing about their own country?

In the real world, the test can have high stakes. Parisa Safa, a math teacher who emigrated from Iran and is now a U.S. citizen, has family members who took the test. “It was a really big problem for them. What if they don’t pass?” These problems are exacerbated for those who do not speak English fluently. “I do have family members who … didn’t speak English. They memorized [the test] … It was a process,” Safa said.

“This is not a requirement for born citizens and it shouldn’t stop people from seeking safety in the U.S.,” Ciara Howard ‘24 said.

Some also find the test’s questions as merely another form of propaganda, promoting a one-sided, overly patriotic view of the U.S. “To enforce these ideas when America can be so hypocritical is disappointing and disgusting,” Linda Ye ‘24 said, who helped her parents and grandparents study for the test.

However, for many, correctly answering these questions is simply a small final step in a larger, more complicated process. “Citizenship is the end of the road,” Safa said. “To become a permanent resident of the United States … it takes up a good chunk of your time and a good chunk of your money. You absolutely need a lawyer.”

In an interview with The Urban Legend, Randy Feldman, an immigration lawyer from Massachusetts, said that for most of his clients, the test is not very meaningful — and it does not need to be. “We might care deeply about the interpretive aspects of understanding what goes on around us … but the person who is typically taking that [citizenship] exam just wants to be a U.S. citizen.”

With enough studying, people from many backgrounds can pass the test (assuming they can become a permanent resident). “My clients, some of which will only have a sixth or 10th-grade education, can generally pass this test,” Feldman said. “They make it easy … if you’ll study,” he said.

As for Urban’s underwhelming performance, Feldman believes that not knowing much before studying is normal. “I only got half of the questions right, and I had just finished law school,” he said.

However, Safa has a slightly different sentiment. In many cases, those who are immigrating to a new nation have gained a deep understanding of their new country while making their decision to move. “As a foreign person, you probably know more about your adopted country than someone who lives there,” Safa said.

“[U.S. citizenship is] something that a huge percent of the world population dreams of having, and you all are just handed it. You don’t appreciate what you already have,” she said. “You [all] know a lot of things … you’re just young and your attention is elsewhere. It’s normal to take your privilege for granted.”