The impact of affirmative action

Affirmative action has been banned in the state of California for 25 years, and it is potentially facing a nationwide ban.

Affirmative action was first implemented in 1961 by John F. Kennedy and later expanded by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965. Kennedy issued an executive order that prohibited discrimination based on “race, creed, color, or national origin” when hiring within the government. Both Kennedy and Johnson believed the best resolution to the uproar of riots following Martin Luther King Jr’s death was to incorporate Black men and women into predominantly white workplaces and higher education. Succeeding these orders, there was a significant surge in diversity within colleges, as well as businesses, but as the riots dissipated, so did the increasing admission of economically and racially diverse students to exclusive universities.

Cornell Law School said, “[Affirmative action is] a set of procedures designed to; eliminate unlawful discrimination among applicants, remedy the results of such prior discrimination, and prevent such discrimination in the future.” The constitutionality of affirmative action is being tried in court beginning on October 31, 2022, but this is not the first time a claim has been made that the practice itself is discriminatory.

In 2003, two cases questioning the lawfulness of affirmative action at the University of Michigan were brought to the Supreme Court by three white students. In this hearing, the court stated there could not be a diversity quota when admitting students. However, the court claimed it was acceptable for universities to try to achieve educational diversity.

Journalist Adam Liptak, in an interview for the podcast The Daily, said, “Educational diversity is the idea that students learn better if lots of viewpoints and backgrounds are represented.” He also said that this diversity is not to be seen as a remedy for systemic issues, but rather something that aids everyone’s learning.

Affirmative action has been successful in offering increased opportunities to students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. “Most colleges were specifically founded to maintain an existing structure of power. Affirmative action is one thing that attempts to account for this, but it’s not the only tool nor does it fix everything,” said Lauren Gersick, one of the college counselors at Urban.

If affirmative action is fully removed from college admissions following the upcoming hearing, there will be a highly negative impact on students of color. In 1994, 60 percent of selective colleges reported the use of affirmative action according to the Department of Education. By 2014, that percentage had dropped to 35 percent.

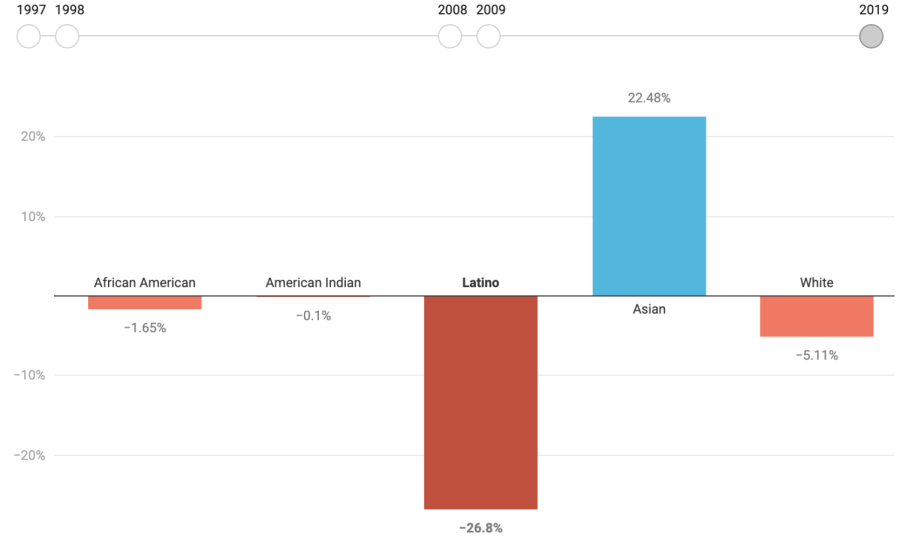

In California, the abolition of race-based admissions in 1996 caused the population of Black and Native American students to fall within public universities, but the group most drastically affected by this change is Latinx students. Edsource reported on enrollment gaps across different racial and ethnic backgrounds and found that although Latinx students make up 52 percent of high school graduates in California, they only represent 29 percent of college freshmen. As of 2019, Edsource reported that Latinx students remained highly underrepresented in university classes.

At the most elite schools in the University of California system immediately following the state ban, the population of Black students also dropped from 7 percent to 3.93 percent, according to The New York Times.

Randy Li, an Urban math teacher, said, “[Affirmative action is] making sure that students who can make use of this [affirmative action] and need these opportunities, get them.” Affirmative action aims to provide students coming from schools with fewer resources an increased chance of receiving higher education. Li said, “Affirmative action looks at who made the most of their academic situation—who took advantage of everything that was offered to them to maximize that situation?”

Despite the controversy sparked in 2019 by the Varsity Blues Scandal, unlike affirmative action, admission processes such as legacy, athletics recruitment and donor preferences are not being contested in the courts. A 2020 National Bureau of Economic Research study found that only 25 percent of white students admitted to Harvard on the basis of athletics, legacy and donor preference would have been admitted if they were treated as a regular applicant. However, this study also found that removing race, legacy and athletics-based admissions—moving to a solely merit-based admissions process—would have resulted in a Harvard class that was just as white. Systemic issues of education access and resource allocation still determine entrance to higher education, some argue that affirmative action aims to solve this.

Affirmative action has also been marketed as a culture war between minorities. In 1980, Asian American students found that the acceptance rate of Asian American students at top-ranked universities was disproportionately lower than the number of Asian American applicants. These students claimed that racial quotas were being used in college admissions and were negatively impacting their community. According to Dana Takagi, a professor at UC Santa Cruz, conservatives against race-based admissions used this as an opportunity to legitimize their cause by pitting Asian American students against Black and Latinx students. In the book “Asian Americans and Politics,” Claire Jean Kim said, “Conservatives transformed an issue of white discrimination against Asian Americans into one of Black ‘reverse discrimination’ against the same.”

Adam Harris, writing for the Atlantic, said, “The primary responsibility for repairing the legacy of higher education, however, lies with the government.” He believes public elementary and middle schools must receive more funding in order to provide students with equal opportunities. Harris said, “The country has provided again and again for white students. Now it must do the same for those whom it has held back.”