Worms, soil toxins, and the Navy: Grace ‘22 and Caroline ‘22 on their environmental racism research

Two Urban seniors, Grace Nesmith ‘22 and Caroline Wu ‘22, are wrapping up a research project where they looked at differences in the prevalence of toxins in the soil of the Bayview Naval Shipyard and Crissy Field. Both environments were historically used by the U.S. Navy. Crissy Field has been remediated — a process which removes contaminants in soil– but the shipyard has not. They found the shipyard’s soil contained significantly higher levels of lead, chromium, and mercury, all of which have negative health implications, than Crissy field. Given the regional differences in socio-economic status and racial demographics, Wu and Nesmith were particularly interested in identifying a correlation between environmental issues and racial and socio-economic factors. I spoke to both of them about the goals of their research, what they hope to achieve with their results, and how they would like to see Urban students engage with this issue. The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. All facts mentioned have been corroborated by The Urban Legend.

What is the goal of your research?

Caroline: The goal of our research was to underline systemic inequities focusing on socioeconomic and racial differences in San Francisco. We specifically looked at Crissy Field and the Bayview, the Bayview being a drastically different racial and socioeconomic demographic than the Crissy Field area. We were hoping to highlight systemic inequities by using those two environments. We were able to connect local history and present day disparities to a scientific research project, and our goal and end result was to have data that can represent these disparities to hopefully lead to change.

You mentioned that you were able to connect these two areas’ histories to current disparities. Can you share the relevant histories?

Caroline: Crissy Field was a naval air base. It was remediated. A lot of toxic chemicals used to be there, but the soil was refreshed and today it’s a natural public green that many people enjoy. The demographics of the Crissy Field area are predominantly higher socioeconomic status and predominantly white, which is not to say that those are always correlated, but that is the particular demographic of that area.

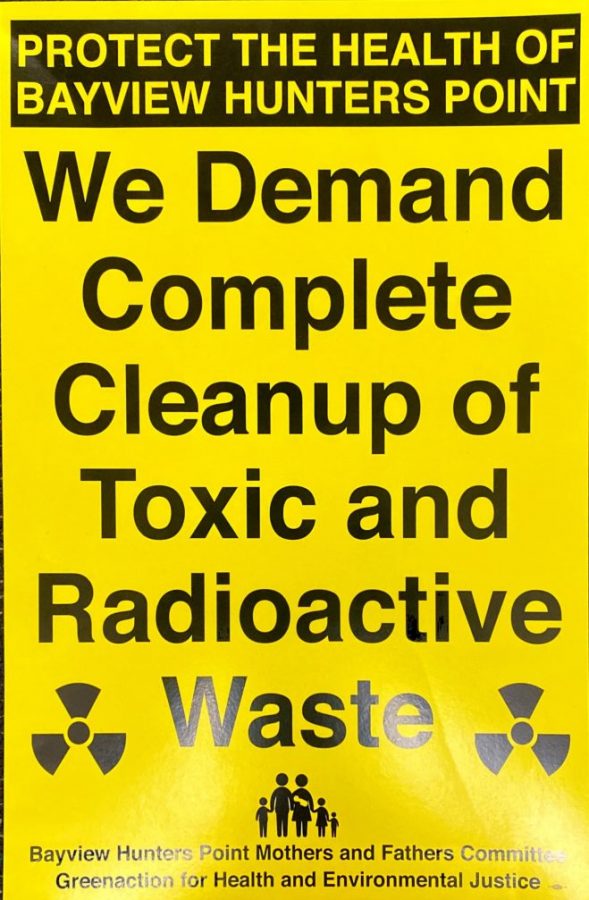

Grace: During World War Two the U.S sent out 49 ships into the middle of the ocean to conduct nuclear bomb testing. In setting off these nuclear bombs, the radioactive material contaminated the ship’s surface. If you see photos, you can actually see the radioactive smoke touching the boats. And then, these boats were sent back to the Bayview-Hunters Point Naval Shipyard. Bayview-Hunters Point is one of the last San Francisco areas with a large Black population. It is geographically enclosed by highways, so decontaminating the radioactive boats created a lot of local job opportunities. It was reported that you could hold your hand five feet away from the boats and still feel the warmth of the radioactive material. So, people who were cleaning the boats were contaminated with radioactive materials, as was their community and families when they brought it home on their clothes. Animal testing was also conducted and carcasses were thrown into the soil and water after being given lethal doses of radioactive substances. This contaminated the people, the soil, the land, the water, everything around it, and it is yet to be successfully remediated. As our data shows, there are still high levels of arsenic, lead, chromium and mercury, which are the four radionuclides we tested through soil samples and goes to show this dark history of mistreatment.

How did you determine which toxins to look for?

Caroline: These four [arsenic, lead, chromium, and mercury] are typically found in toxic soil. All of which have negative side effects.

Grace: Bayview-Hunters Point has high rates of cancer, specifically lung cancer, and lower birth rates. These four pollutants can be linked to those health issues.

How do you get your data to people with institutional power? Do you believe legislators are aware of this data?

Caroline: Greg Monfils was here when Sophie Maxwell, the former supervisor of the Bayview’s kids, were here. Through him, I had the opportunity to talk to her. She emphasized the importance of educating both communities: our Urban community, the Crissy Field community, and the Bayview community. She emphasized the importance of educating Urban students because they are social justice minded and have the power to take action. We are trying to do that, whether it’s presenting our findings to the school or reaching out to the Bayview library to present our findings. After publishing, Grace and I are also hoping to share our published manuscript with legislators.

What are some of the options for improving the solid quality in Bayview-Hunters point? What options do you guys believe in?

Grace: I think the first thing would be acknowledgement. There has been a huge cover up of the actual toxicity of the soil. At one point, the government hired a third party group to come in to do soil sample testing and it was reported that 97.8% of the data was falsified. That allowed a huge company, Lennar Corporation, to build this whole new living area with fancy glass buildings. There’s about one foot of healthy soil under the building that they added with a tarp in between which is semi-permeable and not going to last forever. I think just acknowledgement of and maybe retesting with an organization like Green Action, who does a lot of work in the Bayview, will bring the truth beyond just what we have found and will provide the community with honesty.

How would you like Urban students to interact with this issue?

Caroline: I do think that at the end of the day, it’s hard to understand your role as a stakeholder in our larger community if you don’t see it. So I think bringing awareness through education, but then also asking people to take a little bit of action. At the end of our physical resources class field trip down to the Bayview, our entire class came up with a brainstorm list of how Urban could support this issue. Some people suggested an interdisciplinary class of environmental justice, doing policy writing letters as a U2, or even just having Green Action more involved with Urban students, because they are always looking for long term volunteers.

Grace: I think education is first. I did not know about the Bayview before conducting this project and the people I’ve shared it with didn’t either. The Bayview is in close proximity to Urban. I think getting a little closer through education and building that empathy, I think that drives a lot of change.

What have been your biggest personal takeaways from this experience?

Caroline: I think the biggest takeaway is that you can sit inside a classroom and learn that your actions have consequences. But really being in a physical environment and seeing the repercussions of individual choices and seeing the neglect, abuse and hurt caused has made me think about where I fit into all that. And where I can work to bring other people out of that hurt.

Grace: I think it’s informed a lot of individual choices I make now, as Caroline alluded to, because it demonstrated the inextricable connection between humans and the environment. And how you can’t really separate the health of the land and the people because, here, the misuse was directly correlated to the maltreatment of both.