A deep-dive into the twisted and confusing world of the world’s most dangerous conspiracy theory

On June 15th, 2018, a man named Matthew Wright blocked the Hoover Dam Bridge with a DIY armored truck, holding a sign demanding that the Office of the Inspector General release its report on the Muller findings, a common demand at the time from QAnon believers. This event cast QAnon into the mainstream. So what is this viral conspiracy and why does it matter? A VICE analysis pegged the estimated number of QAnon followers as 10% of the U.S. population or 33,000,000 people. But what do these people believe in and why does the general public know so little about it?

On June 15th, 2018, a man named Matthew Wright blocked the Hoover Dam Bridge with a DIY armored truck, holding a sign demanding that the Office of the Inspector General release its report on the Muller findings, a common demand at the time from QAnon believers. This event cast QAnon into the mainstream. So what is this viral conspiracy and why does it matter? A VICE analysis pegged the estimated number of QAnon followers as 10% of the U.S. population or 33,000,000 people. But what do these people believe in and why does the general public know so little about it?

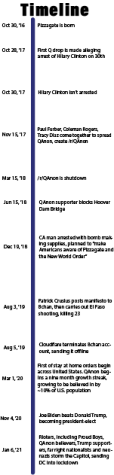

On October 28th, 2017, an anonymous user posted a message to popular anonymous message board 4chan claiming that Hillary Clinton would be arrested the following Monday on October 30th. This was the beginning of Pizzagate, a conspiracy theory that claimed Hillary Clinton and other high-ranking Democratic officials were involved in a child trafficking ring orchestrated out of a DC pizza restaurant called Comet Ping Pong. Pizzagate would eventually culminate in a man showing up to Comet Ping Pong with a loaded AR-15. Pizzagate later evolved into what is now known as QAnon: a global conspiracy theory that alleges a cabal of child-eating pedophiles controls the world. QAnon pushes the idea that the “deep state” is part of this cabal, and that former president Donald Trump was the sole man who could defeat this deep state and dismantle the pedophilia ring.

“It is a classic New World Order Type of conspiracy theory,” says Travis View, host of the QAnonAnonymous podcast, which disproves and covers various parts of QAnon. View has been reporting on QAnon since July of 2018. Q followers believe that “were it not the election of Donald Trump” this satanic, new-world-order, pedophilic, child-eating sex cabal would have continued to rule the world and grow in power. QAnon—the movement—is centered around posts on anonymous imageboards such as 4chan, 8chan and now 8kun by a user who goes by “Q.” Q’s posts are called Q drops or breadcrumbs. Q drops started out as incredibly cryptic, puzzle-like series of questions, but evolved into more declaration-like statements. There are many theories about who Q actually is, but no one is 100% sure. Following all Q drops is very difficult, especially because of their cryptic nature, so most people who are considered subscribers to the QAnon theories rely on other people who read and interpret Q drops. These middlemen are known as bakers. QAnon has grown into a community of its own: There are QAnon YouTubers whose channels are dedicated to talking about new Q drops, interpreting Q and debating the meaning of the contents of Q drops. There are also Q Facebook groups, Telegram groups, meetups, rallies and more.

QAnon has a massive following in the U.S., but its international following poses an arguably more immediate danger. QAnon has enjoyed a substantial rise in popularity in European nations, but its growth in Germany is perhaps the most concerning, given the similarities between QAnon and a 20th-century antisemitic fictional book called The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The Protocols claim that the Jews have a plan to take over the entire world, that Jews pull the strings of government, capital and the economy, and are trying to destroy the state for their own gain. The Protocols, which originated in early 20th century Russia, has been translated into many languages and has had very real-world implications. Both Hitler and Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels read and praised the text. QAnon and The Protocols are very similar. Both allege that there is an elite group who either does or is about to assume control of the world. For The Protocols, it’s the Jews, and for QAnon, it’s the deep state (which in most cases is used as a dog whistle for the Jews). The danger comes from the fact that QAnon followers are almost all evangelical Christians who are conspiracy prone and at the very least unconsciously antisemitic. View says this should be cause for alarm, as “a grassroots antisemitic movement, I think is always something you need to keep your eye on.” According to a New York Times article, German counter-terrorism officials are keeping a close eye on the movement within Germany.

Few thought QAnon would ever hit the mainstream, and many people definitely didn’t expect someone who openly believes in Q to be elected to the House. U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, who openly supports and amplifies QAnon, was elected to represent Georgia’s 14th congressional district in the 2020 elections. QAnon also played a large role in the January 6th Capitol insurrection, says View, who argues it was “fueled by QAnon because it created this environment in which people felt comfortable believing absurd things and put total trust in the president [Trump].” This isn’t to say QAnon as a movement or Q as a person should be considered fully responsible for the events of January 6th, but some blame definitely should be attributed to the conspiracy for priming people to see the word of Donald Trump as the word of God.

To most people, QAnon seems impossible to believe. Believers seem to have a blatant disregard for logic. None of the QAnon beliefs pass Occam’s razor. The big question is how QAnon became so widespread. View says much of the blame for its sudden popularity should be placed on social media companies, specifically Facebook. “If someone was on one kind of conspiracy theory site group on Facebook, the Facebook recommendation algorithm would suggest QAnon groups to them,” says View. View says Facebook wasn’t just ignorant, they were complicit and profited from QAnon by not just providing a platform but essentially providing free advertising. Twitter’s recommendation algorithm also leads conspiracy-prone people down the Q rabbit hole by suggesting QAnon related accounts. Social media platforms “have a great deal of blame for amplifying QAnon way more than it would have been if they even just didn’t recommend the content.”

The cryptic nature of Q drops is also partly to blame. QAnon believers are made to believe “that they are patriots who are helping take down the cabal, and they can help bring about these incredible revolutionary changes in the country and in the world,” says View. The gamification that comes as a result of Q drops being cryptic certainly makes it addictive as well. QAnon believers are also often ostracized from their families, friends and communities for their beliefs, meaning the only people that they have left to turn to are people who also believe in QAnon, which only pushes them further into a detached, QAnon-centric view of reality. It’s also incredibly difficult to deradicalize people who believe in QAnon, says View, partially because “often they make a great deal of sacrifices for the sake of a belief system sometimes like, you know, they devote hours of their life at their computer, sometimes sacrifice family and friends, and then it’s just very painful to realize that all of those sacrifices are for absolutely nothing.”

Even more mysterious than the content of Q’s posts is Q themselves. So far, nobody has been able to prove who Q is. The fact that the style of Q drops has changed hints that the Q handle may have changed hands at some point. There are many theories, some more plausible than others. First, there’s what QAnon believers believe: Q is someone who holds Q level clearance at the Department of Energy or is someone high up in military intelligence circles. They believe that Q has close contact with Donald Trump. Then there are the other theories. The theory that seems most likely is that Q is a member of the Watkins family, who bought 8chan from Brennan in 2014. The main pusher of this theory is 8chan founder Fred Brennan. Brennan left 8chan and stopped working with the Watkins family in 2018 after Jim and Ron Watkins began embracing Q. Brennan recalls Ron Watkins being very excited about Q moving from 4chan to 8chan. Brennan believes that Q wasn’t always the Watkins, but since Q moved onto 8chan, the Watkins took control of Q’s account and started making posts as Q.

President Biden’s election and subsequent inauguration seem to have triggered a winding down of the movement. Q stopped posting abruptly and without warning. The last Q drop was on December 8th, 2020. Brennan believes that Q stopped posting out of fear of legal repercussions. “With the Biden administration now in power, because what they’re doing is illegal. They’re impersonating a federal agent,” says Brennan, “and even though this law was not enforced by Trump, I believe they’re afraid Biden will enforce it.” If Q continued and was prosecuted, 8chan could be subpoenaed, requiring them to hand over server logs, which could potentially expose Q’s identity. “The Watkins are just deathly afraid of the authorities,” says Brennan.

Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Spotify, Apple and more have collectively purged hundreds of thousands of accounts and millions of posts and comments promoting QAnon, although Brennan thinks this is too little too late: “When there are terrorists inside the Capitol, it is too late to ban QAnon on Facebook and Twitter. That is, years and years after this should have been controlled and taken care of.” Brennan also thinks the media has failed to adequately report on QAnon. Brennan says mainstream media organizations haven’t invested enough in familiarizing themselves with the internet and internet movements: “we need to move past this idea where we pretend it’s normal to be ignorant on internet topics when you’re in a major media that is, that is killing our society, it is no longer acceptable for a mainstream reporter to not have a basic grasp of the internet.”