The challenges of teaching at Urban: a veteran perspective and a new teacher perspective

Students and parents of students enrolled at Urban were asked to rank 20 factors that helped determine their high school decision. The top two responses were related to Urban’s faculty. According to Urban’s 2016 admissions survey, sent by the Urban admissions team, 83 percent of Urban families ranked teacher-student relationships as extremely important, and 78 percent ranked quality of faculty as extremely important when evaluating different high schools. It is well-known that being a student at Urban is academically challenging. Equally as difficult, however far less discussed, are the challenges of being a teacher at Urban.

In response to a question about the recent loss of History Teacher Cheri Martin and Chinese Teacher Yi Jiang, Jonathan Howland, Dean of Faculty, said, “It’s never happened before in the history of this school … so the fact that it has happened twice this year is rather jarring and stressful … I can’t talk about those specific circumstances … but what I can tell you about very happily is what a great place … (Urban) is to teach, and also how hard it is.”

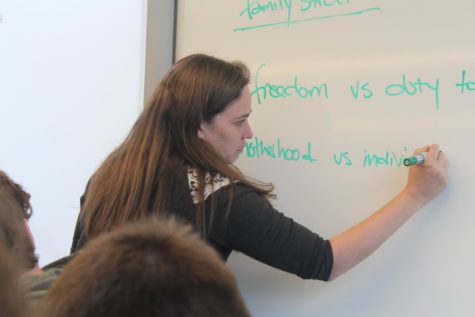

“(Teaching at Urban is) not for everybody,” Howland said. “You have to have a depth of knowledge and subject expertise and aesthetic passion for your subject. You have to be a true expert and a real nerd.” A curious and inquisitive student body demands a well informed and passionate faculty. At Urban, there is a level of collaboration between teachers that is fairly unique to the school. Howland said, “Urban teachers are teachers of students as well as students of their own teaching – always, and often in consort with colleagues, re-thinking and refining their practices to better understand and facilitate great learning.”

Math Teacher, Scott Nelson, who started teaching at Urban in September of 1986, sees many consistencies in Urban’s teaching today compared to Urban’s teaching three decades ago. When asked how he ended up at Urban, Nelson said “I fell here. I didn’t get drawn here.” Nelson came back from Nepal looking for a teaching job in San Francisco. He was splitting wood at Hunter’s Point and when he got a call from a school he had never heard of: Urban. “I thought it was called the Irving School,” he said.

In 1986, when Nelson first came to Urban, the school had 162 students, and they had just begun connecting the Gumption building to the next building over. Nelson used to call Urban “The One Staircase School” because the only staircase back then was the one next to School Counselor Kaern Kreyling’s office.

“What’s cool about The One StairCase School,” recounted Nelson, “is you saw everybody everyday several times, because there was only that one staircase.” Even though the class sizes were the same as they are now, Nelson knew almost everybody in the school.

With classes ranging from about 12-16 students, that aspect of teaching at Urban hasn’t changed much.

“They told me there was no textbook and no curriculum and that I could teach whatever I wanted. .. that was awesome and terrifying,” said Nelson. Despite being intimidated by what he described as “beautiful freedom,” he drew inspiration from the teachers around him. “I was awed by the teachers that were in the building … There was a passion for teaching and learning and it was very clearly in the building,” Nelson recalled.

Nelson said, “Wow this place can really teach. I hope I can keep up.” After about three decades here, not only has Nelson kept up, but he has endured major changes for Urban teachers. One major change was the introduction of grades to the Course Report in the 2011-12 school year. Although students have received a conventional transcript with letter grades since the school’s founding in 1966, it was just a few years ago in the 2011-12 school year when letter grades were added to the tri-annual course reports.

“The biggest difference is in the relationship of the students to teachers which really has to to do with grades and the college pressure that I notice,” said Nelson. He attributed these changes to the external world, not Urban itself: “It’s not like we have changed as teachers or what we care about, it’s just the world has changed.” Despite this externally motivated shift to have a more college focused high school experience, Nelson sees Urban teaching as fundamentally the same: “It’s tremendously challenging.”

“The standards are very high,” said Nelson, partially connecting these standards to how “the students demand excellent teaching … What’s easy about it is for the most part students like to learn,” mirroring the passion Nelson describes in his colleagues.

“What’s hard about it is [students] ask really hard questions, you have to really know your stuff,” Nelson said. Students expect teachers to have a high level of expertise in their subject, which Howland described as central to being a successful Urban teacher. Students’ passion for learning demands a vast depth of knowledge for the teachers to be equipped to deal with tricky questions from curious students.

One change Nelson saw as beneficial to the Urban community is that teaching has become more professional. Nelson partly connected this to Urban’s increased standards for hiring in order to develop a stronger staff. He also saw the school’s increase in popularity and success as a factor adding to this professionalism.

“Teaching responds to the demands,” said Nelson, “we have higher demands from parents, higher expectations for test scores being good when we never even talked about test scores. We didn’t care about AP classes or test scores.” A heightened focus on test scores demanded that Urban teachers adapt to a more formal style. “I don’t think it ruins us, we saved our soul, you know.” Nelson believes that teachers and teaching at Urban has endured superficial changes, but has remained fundamentally the same. He even thinks that by prioritizing depth over breadth of subject matter Urban still doesn’t really teach towards testing.

Not all of the challenges are limited to class time. The Urban standard for feedback on students’ assessments and tests is also very high. Before coming to Urban, Nelson taught at a public school for three years, where he worked with 150 students a day. When he came to Urban, he taught about 40-50 students per day. Despite having far fewer students, Nelson said, “I spend about five times as much grading time here than I did in the public school.” Grading for Urban teachers can be a highly time consuming activity. “To grade one set of tests in math here might take me three hours,” Nelson added. But, Nelson concluded, “We focus on learning more than grades.” Nelson summed up teaching at Urban by saying, “It’s very high energy and intense and wonderful, and super hard.”

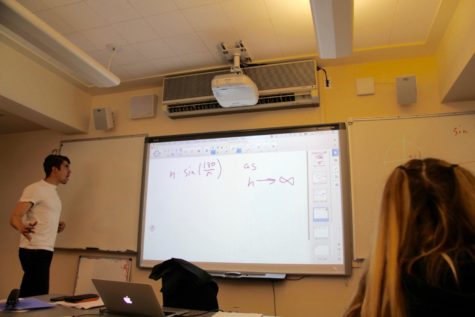

Math Teacher Jessica Yen also taught at a large public school before coming to Urban. Yen worked at a high school in northern Virginia for four years before she moved to the Bay Area a year and a half ago. She taught about 30 students in a classroom, compared to Urban’s average class size, 14 per classroom. A different class size demanded a new style for Jessica. “The teaching style here is much more hands on, there’s a lot more discovery learning,” she said. “As a teacher your role is more around how to guide students towards that learning,” she continued. Yen said that planning for a lesson is harder because there is so much more class time.

At Urban, Yen adapted a new style of teaching math even though she had been teaching for several years already. She explained that “The activities we do (at Urban) are very unique and really help students to understand concepts more deeply but it’s definitely a non traditional way of looking at things.” Originally, she was daunted by this new approach but she is glad that she adjusted to a new style.

Urban teachers are faced with the challenge of fitting a semester worth of curriculum into a 12 week term. Courses move quickly and are fast-paced. Yen said, “pacing was a little bit challenging at first to adjust to.” Yen described another challenge of the 12 week term: there is less time to build relationships with students.

After coming to Urban, Yen has felt more intellectually challenged, and said, “I sit and think a lot more about how to teach math than I did at my previous school.” However, in terms of time management she feels relieved. “Time wise I felt much more sleep deprived at my other school because I would stay up late grading literally hundreds of papers,” Yen recounted. All in all, she said, “The expectations here are higher.”

Just like our teachers demand hard work from students, the Urban community holds very high standards for its teachers. These standards may have developed overtime, but the heart of Urban teaching remains the same, and very challenging.