Could a laser printer save the lives of people waiting for organ donations?

As of 2008, there were 105,567 patients waiting for an organ donation, a nearly sixfold increase from 1998, according to the Department of Health and Human Services Web site at organdonor.gov. Meanwhile, the number of donors during the same period rose only 58%, to 14,630.

Enter organ printing. On March 3, Anthony Atala, the head of the Regenerative Science department at Wake Forrest University, gave a lecture at the Technology, Entertainment, Design (or TED) conference in Long Beach.

As a prop, Atala brought a printer onstage; and 11 minutes into the presentation, he explained that the machine was at that very moment printing a human kidney.

“It takes about seven hours to print a kidney,” he explained matter-of-factly, “and this is about three hours in.”

Karen Richardson, communications manager at Wake Forrest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, described the process by which organ printers were designed, explaining that “five or six years ago, we used actual desktop inkjet printers that were adapted to print three-dimensional shapes.”

A company by the name of Organovo, based in San Diego, has spent the last few years designing what it calls a “Bioprinter,” a large and highly specialized version of an ordinary inkjet printer.

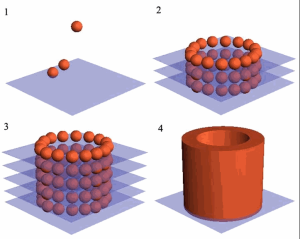

But unlike ordinary printers, the “bioprinter” can print three-dimensionally by depositing layers of liquid onto a thin scaffold of organic fibers that later dissolves. Instead of different colored inks, the cartridges are filled with the components of human tissue. The result? A life-sized organ.

Still, obstacles remain. According to a lecture published on the Web site of the Bioprinting Center at the Medical University of South Carolina, Director Vladimir Mironov wrote that “the manufacturing system is extremely expensive.” Organovo’s NovoGen MMX Bioprinter costs about $200,000 per machine, according to a 2010 Economist article (Organovo does not yet publish prices).

In a 2008 Discovery channel interview, Organovo founder and University of Missouri professor Gabor Forgacs optimistically wondered about the possibility that at some point, someone could “replace (their) lungs because (they’re) a heavy smoker.”

“Well, my first advice is don’t be a heavy smoker,” he added. “But having said that — of course!”