Students reflect on anti-sexual violence social media movement

On March 3, Sarah Everard, a 33-year old marketing executive, was murdered by a male police officer on her 50-minute walk home to her apartment in London. Following this tragedy, a wave of outrage swept the United Kingdom and beyond, inspiring efforts to keep the female-identifying population safe. Everard’s murder has encouraged a broader conversation around sexual harassment, assault and violence that has spread onto online platforms such as Instagram and Tiktok.

“I think social media, especially now in the pandemic, is a great way for teens [to engage in] advocacy,” said Ivy Armstrong ‘22, founder of the activism Instagram account @thereish.o.p.e. Armstrong describes the account as “an educational base for people who are struggling with their emotions after sexual assault,” and a place for people to anonymously share their stories. “When we are talking about something as serious as sexual assault,” said Armstrong, “it’s important to do that through social media, so people can read things and process them in [their] own way because it can be very triggering”

“The main issue is the lack of awareness around sexual assault and harrasment, so spreading awareness seem[s] like the best thing I [can] do,” said Marin Stephens ‘23 when asked why she has partaken in this social media movement. “I had no idea the percentage of women who have been sexually harassed was that high”. The percentage Stephens is referring to is from a survey sent out in January 2021 by the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, UK. The survey collected data from over 1,000 women and found that 97% of women aged 18-24 had reported being sexually harassed in public spaces. This 97% statistic has become one of the most widely shared statistics in the world of social media activism.

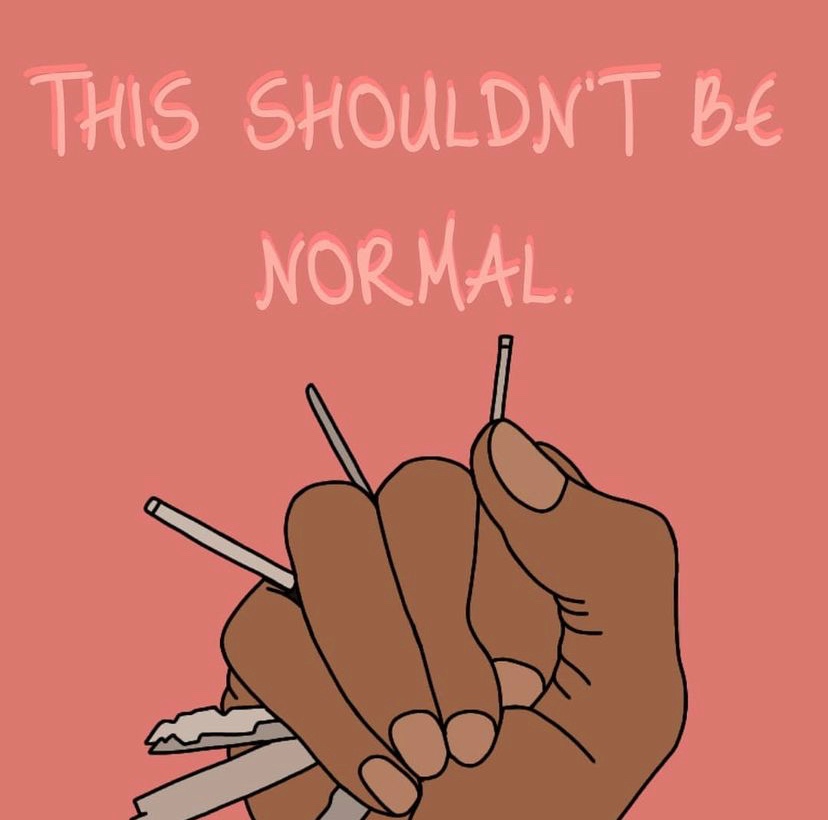

“It’s hard to put into perspective what 97% of women looks like,” said Jack Setrakian ‘21, “but seeing it kind of dumbed down in an Instagram slide can be really eye-opening.” Another widely shared illustration Setrakian found impactful was a drawing of a woman’s hand clenching keys between her knuckles with the title “This Shouldn’t Be Normal.” “When I’m walking on the street, I don’t have to worry about being sexually harassed,” Setrakian said, “so that post was really helpful for me.”

“When scrolling through Instagram stories you see a lot of repetition with posts,” Armstrong said. “You might skip through the first few and then after you see it multiple times you most likely will read it.” Armstrong also said that “there’s a fine line” when it comes to constant reposting because “you don’t want to fully normalize [sexual harassment and assault] unil it becomes a lighthearted topic.”

“I don’t know how you manage spreading awareness about this issue without desensitization,” said Hadley Griffin-Schmidt ‘22. “I would say for the vast majority of these posts it’s the same infographic over and over again and you’re not going to be impacted by that one if it is constant.” As someone who has not participated in this social media movement, Griffin-Schmidt shared some insights into why he has not engaged. “I think it’s a common feeling, but at least for me, it feels almost like a half step,” Griffin-Schmidt said. “I feel a conversation is more effective than an overflow of Instagram stories.”

“I see a lot of girls posting. I don’t see a lot of guys posting,” said Armstrong. “I think it’s something that we as women all experienced at such a young age so we feel more motivated [to post].” Setrakian, Stephens and Griffin-Schmidt all agree that they have not seen many male-identifying people post on their social media accounts about these issues. Armstrong said that when she does see a male-identifying person post she “makes sure to acknowledge that, because with toxic masculinity, a lot of guys tend to hold back.”

“I think a lot of guys feel weird being the one guy that does post so maybe if a few guys took the initiative, there would be a landslide,” said Griffin-Schmidt. He also “tends to believe [that] when a guy posts it is performative.” This notion of performative activism makes it hard to tell when people authentically support the issue or, as Griffin-Schmidt said, are “just doing it to save face.”

“I think you can tell when someone’s intentions are performative,” said Setrakian,“like when someone reposts an infographic and then [makes] a sexual harassment joke, or a rape joke.” Setrakian also thinks it “might be performative if you’re not willing to work towards a resolution.”

“If your intent is performative,” said Armstrong “you shouldn’t post, but the least you can do is educate yourself and read about it.” Armstrong also stresses the importance of finding other ways to be an activist besides using social media. “You can still be an activist by just starting up conversations. You can still be an activist by donating. You can still be an activist by doing so many other things.”

For Setrakian, being an activist off of social media means “being a better ally to female friends, whether that’s showing solidarity or whether that is walking someone home when it’s late. I think if you still truly care, you have to show up in some other way.”