Gods? They’re dead. All those nice things that came with them – immortality of the soul, eternal bliss, lifelong meaning? They’re dead too. Right and wrong, unshakable truths? Dead!

These are the conditions of our secular age. And “all those nice things” turned out to be essential to the pre-modern conception of meaningfulness. So, in the absence of gods, how do we lead a meaningful life?

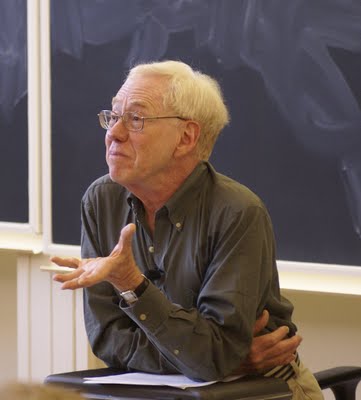

Hubert Dreyfus, a philosophy professor in UC Berkeley’s Graduate School, and Sean Kelly, faculty head of Harvard University’s Philosophy Department, published on Jan. 1 All Things Shining, a book that takes readers on a lighting-paced journey through historical literature in an attempt to resolve the human desire to find meaning in an otherwise chaotic world.

At a recent Mar. 7 event at Berkeley’s UC Press Bookstore, Kelly said that whatever this resolution might be, it will differ “from all the epochs preceding this one.”

“It’s no longer obvious on the basis of what we’re supposed to make the most difficult decisions in our lives,” he explained.

This largely has to do with the way religion has contributed to the axioms of meaning in the past. The truths inherent in faith created a sturdy ideological foundation for people living in an age defined by world religions.

Yet, according to Kelly and Dreyfus, religion no longer plays that all-influencing role. Although it still exists, any one religion is not ubiquitously accepted by default. So God isn’t “dead” per se, but exists on a much less influential plane than before.

Whereas the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche would consider this instability freeing, the average individual might find such boundlessness – or, alternately, emptiness – frightening.

Though they eventually trace a long line from Homer’s works to Moby Dick, Kelly and Dreyfus begin their quest for meaning with a modern, American writer: David Foster Wallace. Wallace, the coauthors claim, “was the greatest writer of his generation,” and “perhaps the greatest mind altogether” because he wrote specifically to show his readers how to live a meaningful life.

As Kelly and Dreyfus quote, Wallace identified “something kind of sad” about being a human being in America at the turn of the millennium – a sadness which, in turn, “manifests itself in a kind of lostness.” The coauthors attribute this mood to “the way our age fails to allow us to tell a coherent story about the meanings of our lives.”

So Wallace, recognizing this, attempted to apply “CPR to those elements of what’s human and magical that still live and glow despite the times’ darkness.”

Dreyfus and Kelly, while writing in admiration of Wallace’s goal, ultimately condemn the results. He had, they note, “deliberately hamstrung himself by choosing the most boring characters imaginable: people who sit for eight hours a day reviewing other people’s tax returns.”

On top of that, Wallace’s proposed solution to “lostness” is practically inhuman – a “mirage,” as the authors refer to it. According to him, “crushing, crushing boredom” is the key to meaningfulness – living “entirely in the Now,” controlling “how and what you think.” Essentially, being able to find life’s magic wholly autonomously, no matter how awful the circumstance. But, according to Kelly and Dreyfus, this detached way of life is simply unlivable – as evidenced by Wallace himself, who committed suicide before finishing his culminating work.

So, instead, the coauthors look back into one of time’s most saturated meaning: the Homeric age. While we, as modern humans, “are skilled at introspection and think of moods as private experiences,” Homer’s Greeks “were open to a world” wholly incomprehensible to us. Instead of understanding humans as free, autonomous agents, thinking and feeling independently, people “saw themselves as beings swept up into public and shareable moods.”

For those familiar with Dreyfus’s background in Heideggerian scholarship, it’s easy to imagine where this idea stemmed from. Heidegger presented his conception of early Greeks in a very similar way, claiming that they experience the “emerging arising, the unfolding that lingers.” Though this seems vague, Dreyfus and Kelly phrased his idea more accessibly: it’s a shared mood that “wells up, takes over, and goes away” – an instant when “everything lights up on a certain situation and nothing else matters.”

The authors use sports as an example. When something amazing happens in a game, suddenly, all of our indecision disappears, and an entire stadium rises in one shocked, joyous way. Something, somehow, possesses us. In Heidegger’s vernacular, it attunes us to a certain mood.

But this example, they point out, is trivial. We don’t see it embodied in our culture at large, and that’s where the trouble lies. Previously, Greek gods were “the attuning ones,” as Heidegger called them, but time has eroded that tradition.

Kelly and Dreyfus go on to document the transfiguration of meaningfulness, invoking philosophical, literary and religious figures – Descartes, Dante, or Jesus, for instance – delving into their distinct contributions to the state of our world, and ultimately arrive at the conclusion that our best hope for a meaningful life is in being attuned to the world. In a sense, feeling open to accept the moments when circumstances carry us away.

The book’s analysis is deep, thorough and academic, but, strangely enough, also mildly dissatisfying. The work spent on All Things Shining is readily apparent, and I would never mean to imply that the authors are incompetent. But something feels just slightly off.

In my understanding, Kelly and Dreyfus attempted to write a book that I’ve been wanting to read for quite some time: one that elegantly weaves the visceral quality of storytelling with the depth of philosophy; one that redefines “pop philosophy” into something wholly complex and meaningful. Speaking with me briefly after the Berkeley event, Dreyfus said outright that much of the book “is Heidegger” – his philosophical works simplified in a mature way. Yet All Things Shining seems like a beautifully flawed prototype for their intended result. Not only that, but I hope it becomes a prototype for a new kind of book altogether – one that is genuinely popular and staggeringly profound.